Herschel graph

| Herschel graph | |

|---|---|

The Herschel graph. |

|

| Named after | Alexander Stewart Herschel |

| Vertices | 11 |

| Edges | 18 |

| Radius | 3 |

| Diameter | 4 |

| Girth | 4 |

| Automorphisms | 12 (D6) |

| Chromatic number | 2 |

| Chromatic index | 4 |

| Properties | Polyhedral Planar Bipartite Perfect |

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics, the Herschel graph is a bipartite undirected graph with 11 vertices and 18 edges, the smallest non-Hamiltonian polyhedral graph. It is named after British astronomer Alexander Stewart Herschel, who wrote an early paper concerning William Rowan Hamilton's icosian game: the Herschel graph describes the smallest convex polyhedron for which this game has no solution. However, Herschel's paper described solutions for the Icosian game only on the graphs of the regular tetrahedron and regular icosahedron; it did not describe the Herschel graph.[1]

Contents |

Properties

The Herschel graph is a planar graph: it can be drawn in the plane with none of its edges crossing. It is also 3-vertex-connected: the removal of any two of its vertices leaves a connected subgraph. Therefore, by Steinitz's theorem, the Herschel graph is a polyhedral graph: there exists a convex polyhedron (an enneahedron) having the Herschel graph as its skeleton.[2] The Herschel graph is also a bipartite graph: its vertices can be separated into two subsets of five and six vertices respectively, such that every edge has an endpoint in each subset (the red and blue subsets in the picture).

As with any bipartite graph, the Herschel graph is a perfect graph : the chromatic number of every induced subgraph equals the size of the largest clique of that subgraph. It has also chromatic index 4, girth 4, radius 3 and diameter 4.

Hamiltonicity

Because it is a bipartite graph that has an odd number of vertices, the Herschel graph does not contain a Hamiltonian cycle (a cycle of edges that passes through each vertex exactly once). For, in any bipartite graph, any cycle must alternate between the vertices on either side of the bipartition, and therefore must contain equal numbers of both types of vertex and must have an even length. Thus, a cycle passing once through each of the eleven vertices cannot exist in the Herschel graph. It is the smallest non-Hamiltonian polyhedral graph, whether the size of the graph is measured in terms of its number of vertices, edges, or faces;[3] there exist other polyhedral graphs with 11 vertices and no Hamiltonian cycles (notably the Goldner–Harary graph[4]) but none with fewer edges.[2]

All but three of the vertices of the Herschel graph have degree three; Tait's conjecture[5] states that a polyhedral graph in which every vertex has degree three must be Hamiltonian, but this was disproved when W. T. Tutte provided a counterexample, the much larger Tutte graph.[6] A refinement of Tait's conjecture, Barnette's conjecture that every bipartite 3-regular polyhedral graph is Hamiltonian, remains open.[7]

The Herschel graph also provides an example of a polyhedral graph for which the medial graph cannot be decomposed into two edge-disjoint Hamiltonian cycles. The medial graph of the Herschel graph is a 4-regular graph with 18 vertices, one for each edge of the Herschel graph; two vertices are adjacent in the medial graph whenever the corresponding edges of the Herschel graph are consecutive on one of its faces.[8]

Algebraic properties

The Herschel graph is not a vertex-transitive graph and its full automorphism group is isomorphic to the dihedral group of order 12, the group of symmetries of a regular hexagon, including both rotations and reflections. Every permutation of its three degree-four vertices can be realized by an automorphism of the graph, and there also exists a nontrivial automorphism that exchanges the remaining vertices while leaving the degree-four vertices unchanged.

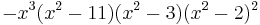

The characteristic polynomial of the Herschel graph is  .

.

References

- ^ Herschel, A. S. (1862), "Sir Wm. Hamilton's Icosian Game", Quarterly Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics 5: 305, http://books.google.com/books?id=-w8LAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA305.

- ^ a b Coxeter, H. S. M. (1973), Regular Polytopes, Dover, p. 8.

- ^ Barnette, David; Jucovič, Ernest (1970), "Hamiltonian circuits on 3-polytopes", Journal of Combinatorial Theory 9 (1): 54–59, doi:10.1016/S0021-9800(70)80054-0.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Goldner-Harary Graph" from MathWorld..

- ^ Tait, P. G. (1884), "Listing's Topologie", Philosophical Magazine (5th ser.) 17: 30–46, http://books.google.com/books?id=8VMwAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA30. Reprinted in Scientific Papers, Vol. II, pp. 85–98.

- ^ Tutte, W. T. (1946), "On Hamiltonian circuits", Journal of the London Mathematical Society (2nd ser.) 21 (2): 98–101, http://jlms.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/s1-21/2/98.pdf.

- ^ Samal, Robert (11 June 2007), Barnette's conjecture, the Open Problem Garden, http://garden.irmacs.sfu.ca/?q=op/barnettes_conjecture, retrieved 24 Feb 2011

- ^ Bondy, J. A.; Häggkvist, R. (1981), "Edge-disjoint Hamilton cycles in 4-regular planar graphs", Aequationes Mathematicae 22 (1): 42–45, doi:10.1007/BF02190157.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Herschel Graph" from MathWorld.